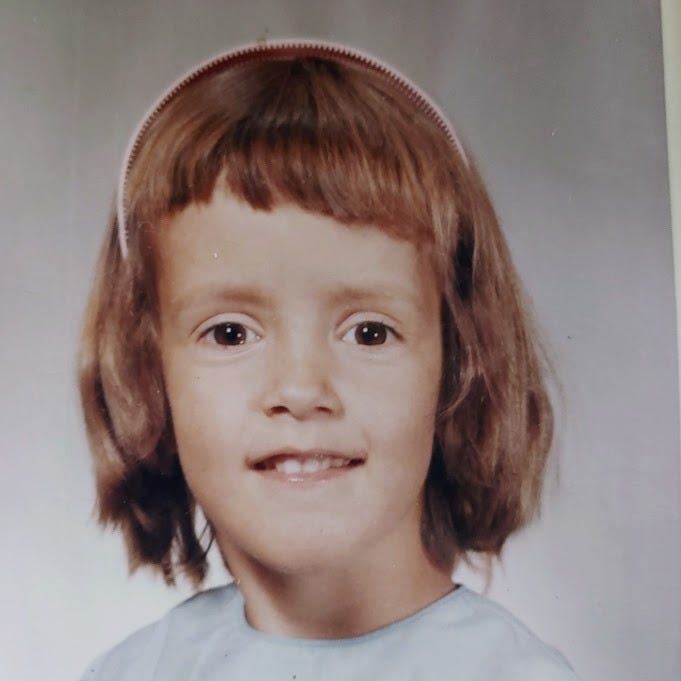

In memory of my sister Laura, whom I never was able to know before she died

I never attended my sister Laura’s funeral. In 1972, at five years old, my parents decided I was too young. We lived in the suburbs of Chicago in a new subdivision, and at the time my mother made calls to neighbors, asking if someone could watch me while the rest of the family went to bury a child. The people we knew best were also attending the funeral, so I ended up in the home of a family down the street who were mostly strangers to me. Everyone understood it was a heartbreaking situation, but no one really knew how to handle it—or me.

I’m not here to dwell on the oddities of my childhood, though. I’m here to share Laura’s story, to honor her life and introduce my children to their Aunt Laura Jean Owings. She was born on August 10, 1959, when the family lived in Columbia, Missouri. At the time, my dad was attending Mizzou after he and my mother left active duty in the Air Force. One in about a thousand children at that time, she was born with hydrocephalus—a condition in which cerebrospinal fluid accumulates in the brain’s ventricles, causing swelling and increased pressure on surrounding tissues. Infants with hydrocephalus often have enlarged heads and may experience headaches, vomiting, or coordination issues. In the late 1950s, treatment involving shunts to drain excess fluid was still experimental, so Laura faced constant medical appointments, frequent hospital stays, and the threat of shunt failures or infections.

Despite these challenges, she was still a little girl who went to school and played with her friends. For my parents, caring for Laura while raising three other children must have been exhausting. Financial and emotional resources were stretched thin, and social support for families with special-needs children was far less developed than it is today. Neighbors and extended family didn’t always understand the seriousness of hydrocephalus, which must have left my parents feeling isolated.

I came along in 1967, and my memories of Laura, I’m ashamed to say, are hazy. I recall numerous doctor visits and a special classroom that seemed more like a hospital ward. Just before my fifth birthday, my aunt was around to look after us for weeks at a time, but I had no concept that my sister was nearing the end of her life.

I don’t recall exactly how I learned of Laura’s death. I’m not even sure my parents ever explicitly told me. I just remember the day a teenage neighbor took me by the hand and walked me down the block to a house where I was given fresh cookies and lemonade. It felt disorienting when I was later picked up and brought to what I now recognize was the funeral reception in another neighbor’s backyard.

After that day, everything felt different. My mother, who was never especially involved in my life, withdrew even more. My father buried himself in work and was often emotionally absent. My brother grew distant, turning to drugs, while my other sister became physically abusive toward me before leaving home at eighteen. It was also unsettling that every photo or reference to Laura simply vanished. I was moved into her old bedroom with no explanation, as though she had never existed.

My thoughts of Laura resurfaced shortly before COVID, when our mother passed away. As the family’s “writer,” I was asked to draft Mom’s obituary. In doing so, I realized I knew virtually nothing about Laura: her exact birth date, how or when she died, even the correct spelling of her name. There were no online records, just the location of her gravesite. It angered me that no one seemed to remember her—no one visited her grave or spoke her name.

Eventually, I went to the DuPage County Clerk’s office for Laura’s death certificate. That’s when I finally learned the particulars of her life and death. I discovered she was buried nearby, so I visited her grave, spending time with the sister I never truly got to know. This summer, I’ll bring my own family to her resting place; my children have never met their Aunt Laura, and she’s right there, waiting to be remembered.

To you, Laura, when I look at the few pictures we have, I see so much light in your eyes. I know you must have suffered through countless hardships, but there’s a spark of joy there, too. I’m sorry you didn’t get more time in this world, and that I never truly knew you. Yet in your eyes, I see hints of our mother—I see the same thing in my eyes, too. I hope we meet again someday in heaven. Until then, I want to honor you here. I love you, and I miss you, Laura Jean Owings.